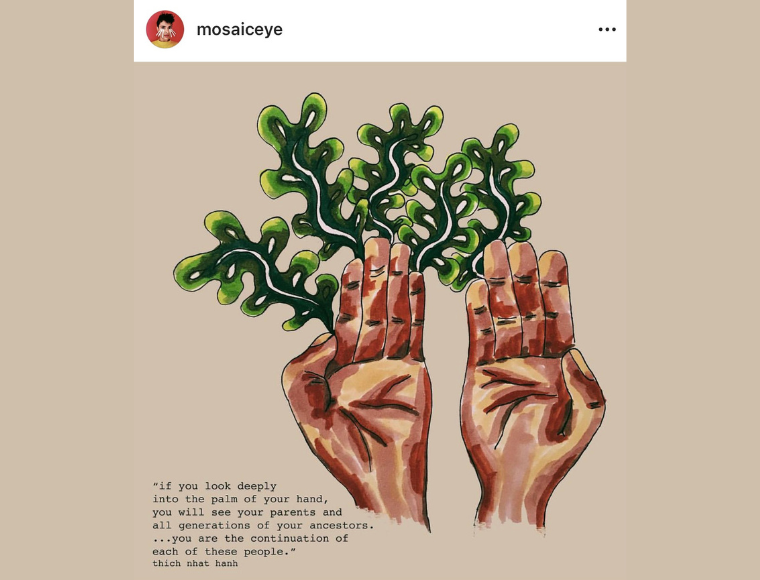

We have not made ourselves.

We are here because something else existed.

In the beginning there were others, and we have followed on from them, picking up new things, relying on what was started, changing and tweaking yes, but always in continuation. So, from whom did we come, and where or to what will this knowing lead us?

I have always asked these questions. As a child, I was curious about the elders and their stories. It is why I am the kind of friend who gets on with your parents, and grandparents. Older people like me perhaps because I have always remained curious about them. I ask questions, and I stay to listen for the answers.

We have not made ourselves, and so we must ask, from whom, or what did we come? The answers I imagine can go as far back as time itself. It feels to me mostly as a calling to unearth those whose names we do not know, and yet, whose blood carries forward, the result of which is an opening of a portal that allows us to return home, back to ourselves.

I think often of my father. Learning to love and hear someone who is here, but not here is why I started re-asking. Nitwe bahi? Who are we? Tukarugahi? From where have we come? My own people are orators. We speak and tell stories, and by so doing, we pass down and teach. Ours demands that tushitame hamwe, tutebye, tuganire. Okuganira, is to conversate, almost lazily, without so much haste. It is to talk about everything and nothing. Nimubasa muganire, busheshe. If the conversation is good, sometimes the day will break, and you will still have more to say. We tell stories to each other, speaking of that which has come and gone, and stayed. We have lost so much, been altered in so many ways, and this allows for remembrance.

My shwenkuru, my father’s father, was one of the lasts in his family to be converted to the church. He had resisted. As a child my father told us stories, and in one of them shared that our shwenkuru had not been allowed any of the ‘holy’ as deemed by the Catholic church sacraments even when he occasionally attended church with them. My father on the other hand, was coming of age at the time they were immersed in learning the language and actions to assimilate, aspiring to leave and change to be accepted into what was now the new normal. People went to church on Sundays and children aspired to speak better English, and leave home. And so, shaped by the changing that was demanded of by a faith in a different kind of God, and a language that was not their own, they changed their names, were baptised, and so accepted. They spoke less and less of what and who we came from.

We are the ones who have decided to return.

When we speak of our histories we are affirming that we have not made ourselves, that we are not the first of our kind. That there have been others from whom we can learn, and who we can teach. It is a reciprocity that allows for us to fill in the blanks left behind by a coloniality that has robbed us of knowing ourselves.

My father was a story teller. He told tales of how they grew up, and always about the mythical-ness that came with the land. I would sit with him and listen for who he had been, who his people were, and who had shaped me, even before I was me. As I get older this knowing that we are more, and that we can return to that feels like deep fuel to my soul. I like to think we can be bridges between worlds and places in times. And so, I am a curator of memories, and I immerse myself into this process with both a curiosity and humility to learn.

We are asking to know, from where do we come?

I did not really know my shwenkuru, my father’s father. By the time I was old enough to know him, he was no longer here. And so, to know him, I am piecing together photographs, and stories. I am listening and seeking out those with whom we shared him. We kept albums as a child. There are photographs of people whose names I am learning. Moments captured at a point in time that allow me to be able to experience with them too. There are photographs of my shwenkuru at graduations of his children, weddings and celebrations. There are stories that his daughters have of him, and as I ask, they share. I am listening, and piecing. In order to return home, to ourselves and to the places, we follow the weavings and crumbs left to us. We search to find.

I am a believer in the concept that we exist not within this singular and linear understanding of space and time, but rather on a continuum. To believe that, is also to know that we have not made ourselves. Titwe abokubanza. We are neither the first, nor the only ones. Instead, we are being shaped, and shaping, with what we can see, and what we can’t. And so, in the returning to this knowing, we remember and repair.